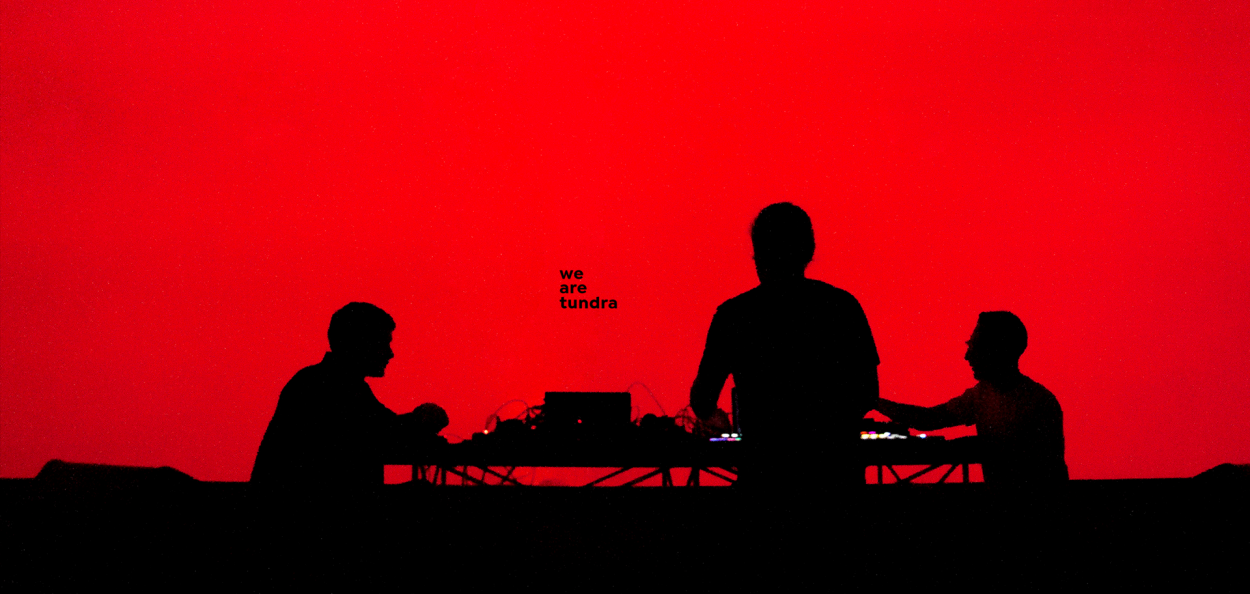

Based in St. Petersburg, Russia, Tundra is an artist collective made up of musicians, sound engineers, programmers, and visual artists in service of creating immersive audiovisual experiences. Their work appears primarily in the form of multimedia installations and performances, which have been shown around the world from Houston to Seoul.

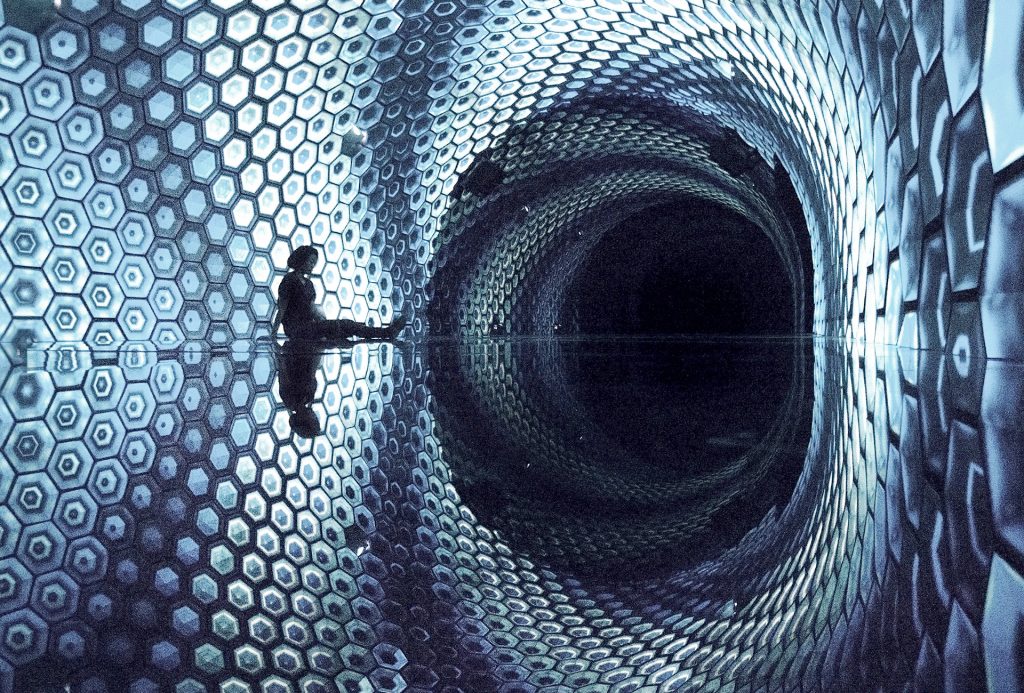

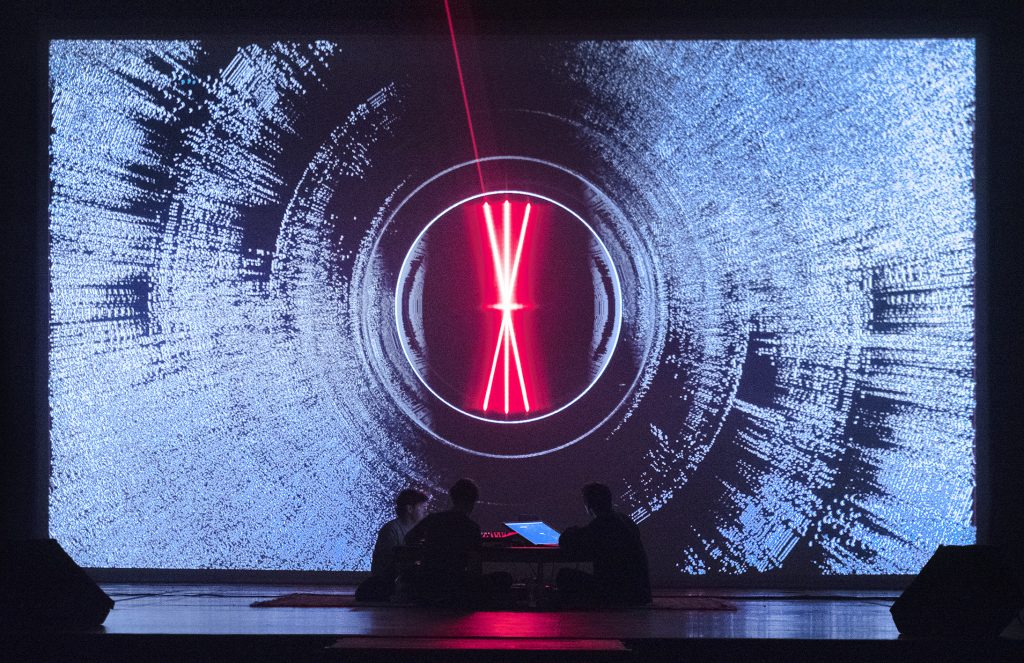

With their work My Whale, for instance, rippling light passes through a long room lined with hexagonal lights, triggered by the rhythms of whale songs playing over the speakers (one iteration of the work was shown on a renovated ship in Moscow). Their 2016 piece Outlines, on the other hand, manipulates a network of dramatic, jittering red laser beams to completely transform the space it inhabits; in their words, this represents “the idea of stepping out of an initial grid and rising above the fundamentals, by trespassing your imaginary boundaries.”

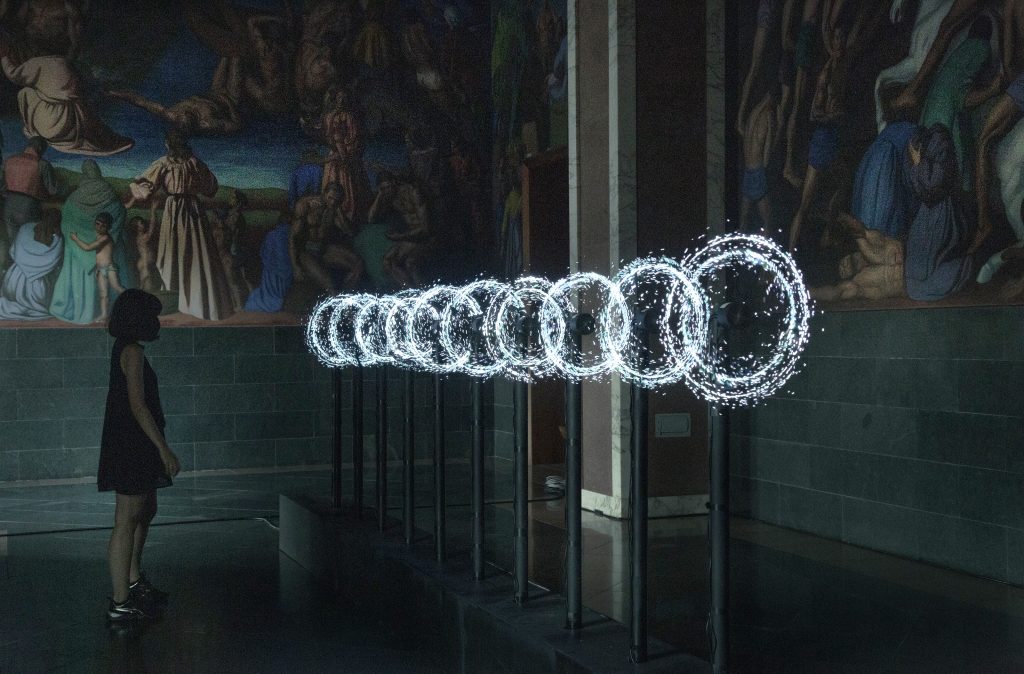

Tundra’s latest work, ROW, is a holographic installation in which LED blades have been hacked to create a holographic row of light, resulting in a range of abstract patterns within this array. These discrete units are thereby no longer seen by the viewer as individual displays, but rather their depth and synesthetic animation build a larger sense of cohesive motion and distance from these piecemeal components.

For our Visual Arts feature series, Evan Shamoon spoke to Tundra about the hybrid nature of their approach, the importance of cross-pollination to their creative work, and how they attempt to impart both meaning and emotion through abstract means.

MUTEK Festival 2018 (Montreal, Canada)

How did you all find one another and decide to collaborate? What are your respective backgrounds?

Tundra started as a collaboration between visual artists and electronic musicians. We met each other in the “Taiga” coworking space in St.Petersburg (2011-2017), where Alexandr Sinitsa’s visual studio and the band D-Pulse’s music studio were located. It was a multidisciplinary coworking space full of DIY stores, designers, developers, typography, and many others. So our background was working with and learning from absolutely different, amazing people.

How does the combination of skills break down and balance out within the group? Do you collaborate with others outside the core trio, or is it easier to keep the ideas coherent with a smaller team?

We do collaborate with other artists on bigger projects, or when it comes to delegate tasks that we are not 100% familiar with—it’s always interesting to explore other points of view and expertise.

As for our core abilities, basically, it’s visual, audio, and its interactions. For each new installation, it’s the programming of a new control environment for generative audiovisual algorithms; this can be done by everyone sitting together in the studio, and being responsible for their software and hardware tools. So it’s like each time creating an instrument that controls light and sound, in the context of an installation space. When visual and sound parameters are synced, we start to fill the narrative with forms and shapes, adding a character and composing a storyline based on a concept. All these elements and abilities are being cross-pollinated and can transform during the experiments and creative sessions, so we never know what the final result will be and what we will end up doing.

Farol Santander 2018 (Sao Paulo, Brasil)

Where does inspiration for a project come from, typically? Is there generally a technical process that becomes particularly interesting for the group, or is it usually something more conceptual?

Inspiration comes from everywhere—typically it’s nature, science, space, music, and new technologies, but in fact, it’s always about physical excitement from actual experiments with new technologies, in the studio or anywhere else.