Orb Sound Lab is a new feature series that explores the art and craft of music production and mastering through the unique lens of forward-thinking artists, producers, and engineers. Rather than taking a generalist approach, the series zooms in on each guest’s distinctive techniques, philosophies, and sonic obsessions, offering insight into how personal artistry and technical precision intersect.

For the first edition, we turn to Peter Van Hoesen, a revered figure in techno and experimental electronic music whose career has consistently balanced deep club functionality with sonic exploration. With the launch of his new mastering facility, Memento Mastering, Peter Van Hoesen shifts focus from personal output to elevating the work of others, applying his production experience and acute listening skills to the final and often most critical stage of the creative process.

In this interview, he discusses how mastering has become a new creative focus, the role of analog gear in shaping sonic depth, and how philosophical intent—empathy, perspective, and clarity of listening—shapes every decision in the studio. The conversation touches on the tactile benefits of analog processing, his favorite gear, and why letting go of ego is at the core of great mastering work.

Let’s begin with the launch of Memento Mastering—what motivated you to start this facility, and how does it reflect your broader journey through sound?

Peter Van Hoesen: It definitely reflects a broader journey. The start of Memento Mastering is inherently linked to the way my music production career has evolved over the years. In the beginning, the focus was entirely on my own output and creativity. The only exceptions were situations where I contributed to other people’s projects, such as composing music for contemporary dance pieces. However, most of the time, the energy was directed towards my personal work, as is the case with many artists.

This changed over the years, and I’ve now come to a point where this focus on my own output is no longer the most important thing. It’s still very much present in my life, and it probably always will be, but there has been a fundamental shift. In a nutshell, I derive more satisfaction from improving someone else’s creations. For me, mastering is the logical step in that development.

Another parallel trajectory is my Patreon page, through which I help producers improve their approach to music production. I have noticed that I really enjoy the process, and that the output of the artist I work with has improved over time. It’s all part of the same idea—putting my knowledge to use in the service of others. By doing so, I feel I’m entering a new phase in the journey. That’s a very rewarding feeling. Memento Mastering is the practical outcome of this shift.

How would you describe your personal philosophy of mastering? What makes it more than a technical process for you?

PVH: There are many ways to approach mastering, but for me, it ties in with what I just said: helping others to improve their sound—the final result of their creative work. In the case of mastering, this starts with being empathetic, with listening to the artist’s intent. Everything begins there.

Of course, there are technical aspects that need to be addressed. One needs to be able to quickly and accurately detect problems in a track and have the skills and processes to fix them. However, I believe this is only one part of mastering. The other part is understanding the artist’s intent and, if necessary, enhancing it.

When you listen with that mindset, it becomes clearer what a track may need beyond technical corrections. Some tracks don’t need much at all—they may be 90% finished by the time they reach the mastering stage. In that case, I handle the technical aspects and aim to achieve the optimal loudness. In other cases, I hear more potential for improvement. It is about helping the track reach its final shape. That’s the creative side of mastering, and it’s something I enjoy immensely.

You’ve chosen to work with a primarily analog mastering setup. From a technical perspective, what do you feel analog gear offers that digital doesn’t?

PVH: First of all, I think it is entirely possible to do excellent work using only digital tools. We’ve come a long way in terms of sonic quality in the digital realm. Compared to, say, 15 years ago, today’s software sounds outstanding. I think it’s important to acknowledge this evolution and the opportunities it gives us. For instance, I monitor using a Trinnov Nova system, which is entirely digital—it sounds absolutely amazing.

That said, I do believe analogue gear still stands out when it comes to adding colour and depth to a track. Without fail, I manage to add that extra fifteen to twenty percent of enhancement using analogue processing. And to me, that’s a significant gain. The cumulative effect of using several analogue processors in a chain is quite remarkable. There’s something about the way analogue processing interacts with our hearing—it seems to create a more engaging listening experience.

There’s also the tactile aspect. I enjoy physically interacting with hardware. It connects me more directly to the sound and improves my creative decision-making.

What role do analog tools play in shaping space, dynamics, and warmth in your mastering chain? Could you walk us through your thought process when using them?

PVH: First, I listen to the track to get a general sense of what might be missing. I might take notes on my initial thoughts, sometimes even writing down a broad approach for that particular session. This is especially relevant if it’s an album.

The next step is correcting any frequency imbalances, usually in the digital domain. The reason is simple: I want to send a clean signal through the analogue chain. Any problematic resonances or peaks are dealt with first, as well as unwanted dynamic spikes. I might go in and automate certain parameters digitally in order to smooth things out. This ensures the best possible result.

In nearly all cases, I use analogue equalisation and very subtle harmonic enhancement. I often work in mid/side mode because I find it a very powerful method for increasing impact and depth. What is important is to know which processors a track will benefit from, rather than just using all of them every time. I tend to be rather selective, sort of a less is more approach.

Is there a specific piece of analog gear that has become essential to your workflow and why?

PVH: At the moment, the Wes Audio NGTubeEq is probably the most essential processor for me. It’s an expensive piece of gear, but it does so many things—and it does all of them extremely well. Whether it’s standard EQing, mid/side processing, or adding a touch of analogue tube saturation, I find myself reaching for it almost immediately. It’s the first analogue processor I turn to, regardless of the track’s character. Sometimes I use it to create more depth via the mid/side option, to add warmth to the low end, or to open up a dense mix that has too much low-mid content. In all these scenarios it delivers. It also has digital recall and several clever features that improve my workflow. It’s simply an outstanding processor. There are sessions where it’s the only piece of analogue gear I use—it’s that good.

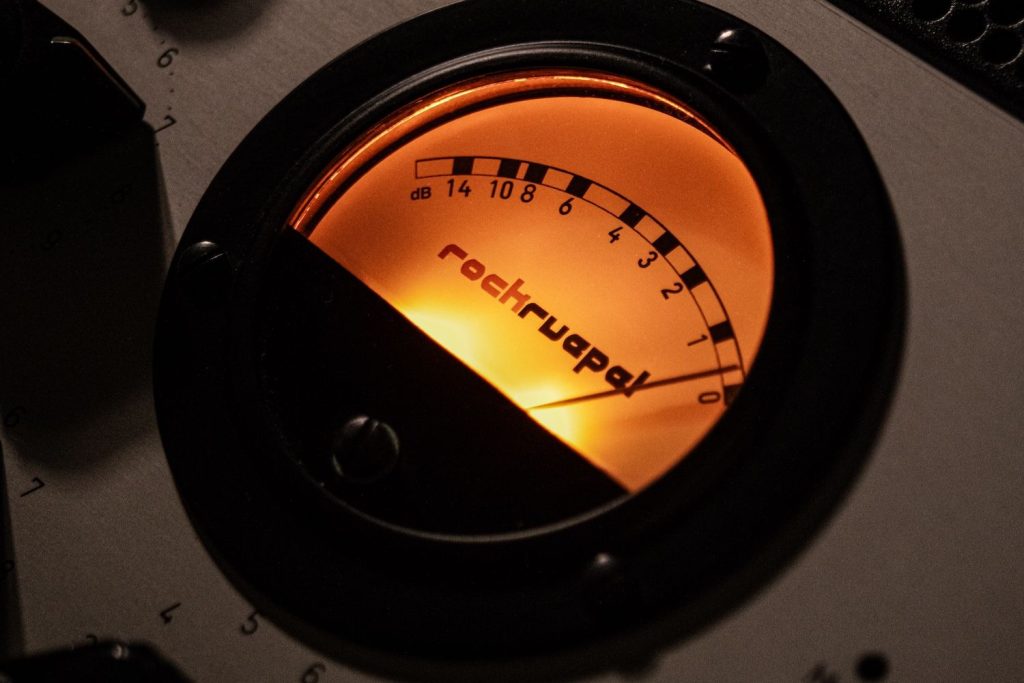

The other essential piece is the Rockruepel Comp.Two, a modern vari-mu compressor that always adds a bit of magic to a mix. I use it very conservatively—usually no more than 1 or 2 dB of compression.

You mentioned there’s a creative and philosophical reason behind your analog choices. Can you expand on that? How does it relate to your way of listening or thinking about music?

PVH: As with the example of the NGTubeEq, I strongly feel that working with analogue equipment encourages a different mindset compared to digital-only mastering. For one, the mind can focus purely on sound. There’s no computer screen or plugin interface to distract you. For me, that makes a big difference.

Our perceptions are prone to biases and mental distortions, and being able to fully focus on the sound is a good way to counteract some of these. Mastering is all about listening—so that’s what should be at the centre of the process. Less visual distraction means more precise hearing.

The advantage of a hybrid setup is that, when needed, you can always rely on digital tools to supplement your perception, or to confirm something you’re hearing. Analogue and digital tools can work together optimally in a hybrid system. It’s not about choosing one or the other. It’s about using them together intelligently. For me, that means using digital as a backup, and analogue as the main part of the process.

Do you see mastering as an extension of your production identity, or something entirely distinct?

PVH: I wouldn’t say anything ever exists separate from the rest. It’s all connected. However, when I’m mastering, I’m not operating from the same frame of reference as when I produce music. Mastering is about being in service to the track you’re working on, and putting your ego aside.

In that sense, you could say they’re two distinct processes. But on the other hand, my experience as a producer definitely informs my mastering work. The knowledge I’ve gained from producing and performing music in different contexts feeds directly into how I approach mastering.

For instance, when working on dance music, my background as a producer, live performer, and DJ helps a great deal. I understand how club sound systems work, and I know what to watch out for and how to optimise a track accordingly.

How do you approach preserving the artistic intent of a track during the mastering stage—especially when you’re working on music that isn’t your own?

PVH: By listening carefully—perhaps talking to the artist, either via email or a phone call, if I have questions. Most tracks are quite clear in what they’re trying to express. If I’m unsure, I’ll ask questions to understand the musical context. From there, it’s up to me to make the right decisions to help the track fulfil its potential.

I always offer the option of a revision, in case the artist has further suggestions after the first version. My job is to make sure the final result aligns with what the artist had in mind. Sometimes that means going a step further and delivering something that enhances the vision.

The fact that I wasn’t creatively involved in the making of the track is actually an advantage. I bring a fresh set of ears that aren’t worn out by hearing the piece repeatedly. Most producers will recognise the feeling of losing perspective after working on a track for a long time. As a mastering engineer, I don’t have that problem.

How has your experience as a producer influenced the way you now work as a mastering engineer? Are there specific habits or instincts that carry over?

PVH: The most important habit is the way I listen. Over the years, I’ve learned to listen to my own music with a degree of detachment, especially from a technical standpoint. This helps me identify issues more quickly.

I’ve produced music in many different contexts: mixing live bands, composing surround works for theatre, performing live, sound design for installations, you name it. All of this adds up and provides a broader perspective, especially when it comes to evaluating how well music is represented sonically.

Looking ahead, how do you envision Memento Mastering evolving? Are there any ideas or experiments you’re hoping to explore through it?

PVH: At the moment, I’m just taking things as they come. It is great to receive many positive reactions from people regarding this new project, and I have had the chance to work with great producers trusting me with their music. That is very rewarding.

In the future, I’d like to start mastering for surround formats. In fact, I already have the speakers and processors ready in storage. It’s just a matter of revising the studio layout and integrating the surround system. That’s a big project I’ll likely begin in 2026.