Embarking on sonic journeys that transcend boundaries and ignite the imagination, the collaborative force of Dorisburg and Sebastian Mullaert weaves melodic tapestries shimmering with poetic beauty. Their boundless artistry captivates listeners, transporting them to realms where genres fade and the spirit of music takes flight.

Dorisburg, the musical alter ego of Alexander Berg, has carved a path of sonic exploration for over 13 years. With each composition, he unveils a tapestry of sound that reflects his unwavering dedication to craftsmanship. From dreamy, melancholic melodies to hypnotic drum tracks, his catalog resonates with a singular personality that captivates both in recorded form and in captivating performances. Within his immersive shows, the countless hours spent in the studio find purpose as Berg effortlessly crafts faithful renditions of his back catalog, interwoven with spontaneous improvisations and remixed versions.

Sebastian Mullaert, a master of musical expression, embraces a distinct approach to life and art. As the founder of the Circle Of Live project and a prolific solo artist, his creative evolution knows no bounds. Rooted in tranquility, stillness, and the convergence of Zen meditation, nature, and creativity, Mullaert’s sonic endeavors elicit a profound resonance. His exploration of modern-classical realms led him to collaborate with the esteemed Tonhalle Zürich, one of the world’s top philharmonic orchestras. Mullaert’s visionary approach bridges the gap between classical and electronic music, introducing a new generation to the enchanting concept of modern-classical fusion.

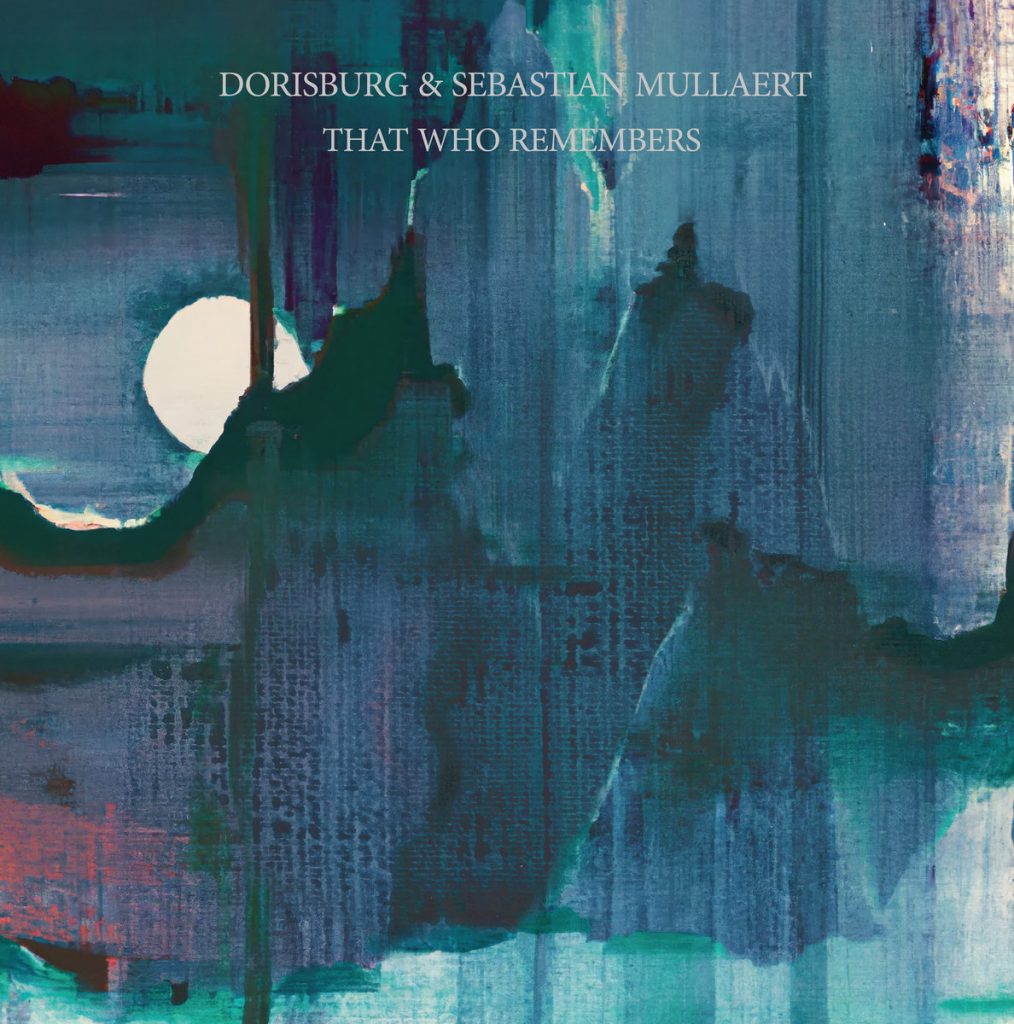

When Dorisburg and Sebastian Mullaert join forces, their combined talents ignite a creative alchemy that transcends the limitations of individuality. Their collaborative albums Bloodwood Moon as Jorum and their latest LP, That Who Remembers—like sonic tapestries woven with delicate intricacy—invite listeners to embark on profound journeys through ethereal soundscapes. Guided by a shared vision, they navigate uncharted territories, venturing beyond the confines of established genres. Their compositions shimmer with a timeless allure, enticing listeners to surrender to the captivating interplay of melodies, rhythms, and textures.

In the following conversation, Dorisburg and Sebastian Mullaert will peel back the layers of their artistic collaboration, delving deeper into their creative process, inspirations, and connection that fuels their musical partnership. As they share their thoughts and insights, more will be unveiled, offering a glimpse into the intricate workings of their minds and shared artistic vision.

Your collaborative journey started with the release of Bloodwood Moon as Jorum. Can you tell us about your initial contact and what sparked the creative connection between you two?

Sebastian Mullaert: Our connection actually started before that. I believe the first time we connected was when I invited Alex to Circle of Live. That’s my earliest personal memory of connecting with Alex. Of course, I had listened to his music much before that, especially the work as Dorisburg.

Essentially, it was Alex’s music that sparked something in me and made me want to connect with him. Circle of Live is a live improvisational concert/club series, and I could envision his music blending perfectly with what I was playing, as well as the music of other artists in Circle of Live.

Over the years, around 2018 and 2019, we performed several times under the Circle of Live flag. During that period, I can’t recall if it was my invitation or a mutual idea, but we decided to meet up in Röstånga and jam in my studio, which led to a five-day jam during the summer of 2018.

We hung out in the forests, took walks, and had in-depth conversations. We also had a number of simple, straightforward live improvisations in the studio. Alex had a few instruments, I had a few instruments, and we recorded everything on separate channels.

Afterward, we didn’t immediately develop those recordings into full arrangements. It was only a couple of years later that we decided to continue the work. At that point, I think Alex came back to the studio, and we spent a couple of days melting and blending, looping those old sounds into more evolved soundscapes.

Dorisburg: I remember Sebastian reaching out about the Circle of Live project, and we had many long phone conversations about music and life. By the time we had our first rehearsals, it felt like we already knew each other quite well. And when we recorded this record we had already performed together in a live setting quite a lot.

How did the experience of working on Bloodwood Moon influence your decision to create That Who Remembers together?

Dorisburg: Actually, our process was very much the same for both. We didn’t enter the studio with a fixed plan for how the music should turn out or whether it would even become a record. It was more about coming together and letting the sounds unfold. We approached it with an open mind, unsure of what we would end up doing with it. Even if it didn’t result in a release, we would’ve practiced and added new material to our live shows, which would have been fine too. After the recordings were done, we noticed they offered many different perspectives on the same source material. It began to make sense to group them together in certain ways and that’s when we could hear how the tracks could fit together as an album.

Sebastian Mullaert: Yeah, I agree. I think Bloodwood Moon has a darker and more intense energy. It has a certain tension and pulse to it, with a sound that leaned toward a more dancefloor-oriented vibe.

That Who Remembers was more like a collage of recordings with a deeper, softer, more mellow vibe. It had a different tone, something gentler and more organic to it.

If I were to describe them in colors, I’d say Bloodwood Moon had a dark purple vibe to it, while That Who Remembers has a sense of green and brown. It evoked a more natural and earthy feel!

Dorisburg: For me, the music has this distinct autumn-like feel to it. A bit like the sounds are coming from beneath the soil, almost as if they’ve been resting there. It’s funny because, as Sebastian already mentioned, we actually did the initial recording in spring or early summer. And the sounds from that session had a quite light feel to them. When we revisited those sounds later, it was the end of autumn two years later. Many of the sounds were run through Sebastian’s tape recorder and slowed down the tempo by half. The recordings sounded like they had gone through this process of decay as if they had been sitting in the soil, maturing and developing in the darkness.

Collaboration often brings together different perspectives and influences. Can you share some of the key musical elements or ideas that each of you brought to That Who Remembers? How did you merge those individual contributions to create a cohesive sonic experience?

Sebastian Mullaert: We went through different steps in bringing these albums to life. The first step, as Alex mentioned, was a completely open moment of just seeing what happens when we meet and record in the studio. No expectations, no pressure, no demands.

For me, a key part of my creative process is allowing my creative expression and excitement to flourish without pushing myself, setting specific goals, or aiming for particular results. It’s about letting the creation unfold naturally. This is also the intention behind Circle of Live. Can we bring this approach to the stage as well? Can we invite each other to embrace this mindset not only when making music or recording, but also when performing in front of an audience? This is a crucial aspect of my overall creative process in everything I do.

Dorisburg: Some projects start with a clear intention of making a certain album before going into the studio. But for us, it hasn’t been like that at all. It’s been more about harvesting sounds and seeing where it leads us.

When we recorded something, we didn’t immediately make decisions about what to do with it. We left that for later, separating the process of creation from the process of deciding what to do with them. It was quite liberating not to have to think about those things while we were in the recording phase.

Sebastian Mullaert: What Alex said about decision-making, or the lack of it, is an important part of my solo creative process as well. To understand that separating these (deciding and not deciding) moments helps to fully allow creativity to flourish. So, when Alex first came, we recorded ideas and sounds without arranging them. When he came the second time we allowed the separated sounds into spontaneously arranged compositions.

I used the same workflow when I recorded the solo album, A place called • Inkonst, and was curious to repeat this process and explore how it was to do it together with another person because this process was so fruitful for me.

Dorisburg: I remember that we would hit record for a bit and take a break, and repeat the process a few times every day. We would record for an hour or so, pause, take walks, and consciously avoid forcing anything too much. It felt effortless because we didn’t enter a state of analyzing or critiquing what was good or bad. We simply recorded sounds and created a library of moods and rhythms that we could revisit at a later time. That later time was when the sounds actually got arranged into an album, but this happened much later.

Sebastian Mullaert: The second time Alex came, we followed a similar process to how I work on my own. I prepared sounds, went to a venue or the studio, selected a few sounds, and then made a live arrangement. As Alex mentioned, there are different steps here that don’t require comparing, judging, or making decisions. When creating sounds, Alex used the word “harvesting” and you then observe how they blossom and grow. We record the sounds as they naturally come out, and there are no good or bad sounds. Every sound contributes to the excitement of the expression.

But of course, at some point comes the moment of deciding which sounds to include in the recording. In our setup, we took our live gear and all the sounds we prepared in the studio to the venue Inkonst. We placed ourselves in the middle of the dancefloor, full volume on the PA. Before each arrangement / live recording, we quickly made choices. The trick here is not to overthink it. And I think when Alex and I work together, we help each other avoid overthinking or getting caught up in analysis. We don’t hesitate or second-guess ourselves too much, asking questions like, “Should I choose this or that? Maybe this is good too.” Instead, it’s quick and straightforward—bom bom bom bom—and then we play.

After that moment of selecting sounds, we arrange and manipulate faders, play instruments, and let the arrangement take form. This step, similar to the first step of harvesting sounds, also embraces freedom from decision-making, judgment, and comparison. The arrangements simply take form. During these sessions, we recorded around 60 songs, although we didn’t release all of them. Deciding what should be included in Bloodwood Moon and That Who Remembers and what might come out later is a separate process that doesn’t interfere with the actual expression. When I listen to the recordings afterward, it becomes obvious—some recordings I feel, either there is attraction or not, and also what recordings that connect with each other are also very obvious. It’s a quick decision, not something that needs deep contemplation or comparison.

Both of you have diverse musical backgrounds and have collaborated with various artists in the past. How did your previous collaborative experiences inform your dynamic as a duo?

Dorisburg: Every collaboration is so unique and it´s both a musical and social interaction, so it´s different each time what workflow works well. However, I believe one common thing is the importance of an environment where it’s okay to experiment, make mistakes, and avoid being too critical of each other.

Without this atmosphere, it’s easy to become constrained or hesitant to express ideas for fear of the other person’s reaction. Or maybe a lack of reaction, that can make you insecure too. There can be all sorts of awkward situations like ending up working on something that neither of us truly enjoys, but no one speaks up.

It’s natural for these things to happen but I think both of us have recognized a few pitfalls that we actively try to avoid.

Sebastian Mullaert: This approach works whether you’re creating music solo or with others. Alex used the word Harvest before, coming back to that, if you view the creative process as something that continually grows and manifests, there’s no need to pass judgment on what emerges immediately.

To me, when working with others, it’s important that we share this mindset. As Alex put it, it’s important to express freely, see what happens, and not immediately label something as a mistake or success. We must first experience the idea as it happens.

Dorisburg: In our case, we made the decision to hit record for a while and just move on, record a new sketch, and move on and we agreed we would not even listen back to the recordings the same day. In the end, we also scraped a lot of stuff but because we didn’t invest any time tweaking the early ideas, it’s not very hard to let go of some of them either. This is unlike situations where you’ve spent a lot of time on a specific sound and it becomes emotionally difficult to abandon it.

Sebastian Mullaert: Exactly! When making music, our entire body experiences rhythms, sounds, frequencies, and emotions. By focusing more on the sensory experience of music than how we think it sounds, we allow ourselves to explore more spontaneous and new ideas. For example, you might suddenly say, “Let’s try this!” and not necessarily know where that idea originated from. This openness to exploration helps us avoid becoming overly cautious or fearful that the other person might not appreciate our ideas.

Dorisburg: I think it’s important to give a collaborative partner the freedom to explore their ideas before questioning them, discuss it, or start making compromises, even if you suspect you won’t like them. I like rather just let them go ahead and try that 100% and see what happens.

It’s easy to make the mistake of trying to find a middle ground when there are differing opinions. Now, with more experience, I find it much more interesting to try opposing ideas to their fullest instead of trying to compromise.

As artists, what do you hope listeners will take away from the experience of listening to That Who Remembers? What emotions, thoughts, or sensations do you aim to evoke through your music, and how does this album reflect your artistic vision and growth as collaborators?

Sebastian Mullaert: Wow, that’s quite an extensive question, but I really liked it. It holds a lot of interesting perspectives.

Dorisburg: When we were recording the album, our goal was to mentally transport ourselves. To aid this, we changed the room’s atmosphere, using things like smoke machines, lighting, and a full club sound system while performing together and for each other. And so I would say I could only hope for the listener to feel transported in some way. Maybe the place they go to in their minds is totally different from what we imagined. I regard many of the tracks as sonic environments that you can visit for a while. If they can go on a listening adventure, wherever it takes them, that’s what I hope for.

Sebastian Mullaert: Absolutely! For me, the whole point of listening to music is to allow the experience of the music to unfold. Allowing art and music in this way is in my opinion as creative as playing or performing, and I feel that allowing your creativity is an important part of feeling complete as a human being. We need to express our natural flow of creative energy, and we can do that even by just listening to music—we don’t necessarily need to play it. And I agree with Alex, an important intention with this album and all other music I do is to invite someone into that opportunity of exploring and remembering one’s creativity, to invite That Who Remembers.