“I’ve been releasing Braindance music as Face Culler since 2012,” said Seattle-based producer Face Culler, who is the creator of the project Procedural Braindance, which dives into the concept of generative music. “It was actually another artist on Occult Research label, who goes by tens (hundreds?) of aliases but is most commonly known as 4rd Armpit or Bewwip, that inspired Procedural Braindance.”

“This was just his immense talent, broad musical background, and many, many hours spent jamming coming together. It was inspiring, but at a time when a single track was starting to take a month or more given my limited time during the day to make music, it made my whole composition process seem hopeless,” revealed Face Culler.

However, Face Culler has managed to compose an entirely new approach to the genre of braindance music. The producer’s day job consists of programming video games, and now he has begun to apply his skills to his work in music by engaging in generative composition. By utilising the procedural systems he develops for video games, he was able to begin implementing his technique with music.

“I’ve written procedural systems for games both at home and at work in the past for generating levels, names, and stories. This seemed like the perfect time to apply that experience to solve my composition time issue,” said Face Culler.

Generative composition is the idea of music being entirely forged by a computer, done hand in hand with algorithms written by the artist, such as Face Culler. Unfortunately, this takes away the ability to be creative with music in terms of it being done manually, yet this new procedure of creating tracks shows a new way of dealing with music making.

“The hours I spend pouring into braindance music, I was able to generate tracks that were as good or, in a few rare cases, better than anything I had ever made myself,” admitted the artist. “And so, it was quite existentially depressed for a bit, but after a few weeks, I got used to the idea. So really, what I’ve done, is I’ve taken my methods of working, my methods of choosing where a fill would go or what kind of melodies I would generate, and created algorithms to reproduce them.”

So what exactly does Face Culler do?

Firstly, it is crucial to comprehend the use of algorithms within the procedural systems. The leading procedural systems are layered with various algorithms to birth a wide array of soundspheres. “If you enjoy compositional techniques such as drawing notes from a hat, or directly translating data from nature (i.e. plants) into note sequences, a layered approach is unnecessary,” said Face Culler.

The producer’s preference in his music bears a maximalist, dynamic approach in which he skips ahead a minute in order to concede significant changes in the mood or the arrangement of the track. Another artist that Face Culler drew his inspiration from is the iconic British artist Aphex Twin. “For example, Aphex Twin’s expansive ‘Mt Saint Michel’ was the track that finally made me truly love IDM during my formative listening years,” said the producer.

It is quite straightforward to create a simple breakbeat with an uncomplicated algorithm. However, in order to produce a cohesive track containing peaks and valleys, a layered approach is more convenient.

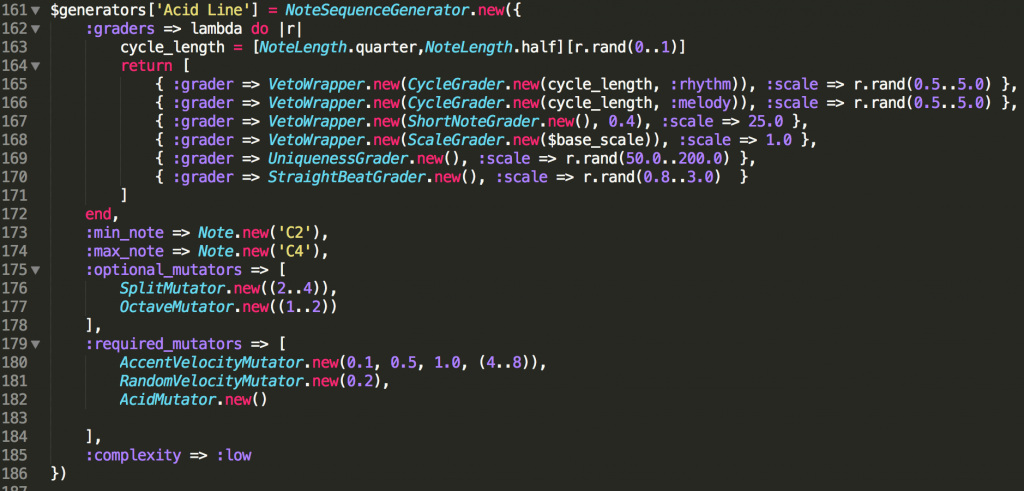

Face Culler designed Procedural Braindance using Ruby, which is a programming language that is astonishingly eloquent which facilitates the transformation and manipulation of data with extensive method chaining. Essentially, the method in which he uses it entails setting up a number of random tracks containing drums, breaks, basslines and melodies, and constructing the parameters and MIDI output device and channels for each. Following the configuration, he sets it to play and records the final product at the end. In a detailed explanation, Face Culler gave us the pleasure of revealing how exactly he produces his music.

“A note sequence is a bar of notes. While forming the sequence, each potential next note (pitch and length, with one option being silence) is graded by a series of what I call graders and only the top 10% are considered.”

There is a variation of different graders that are assigned to a different task. For example, UniquenessGrader delivers high grades if a certain note has not appeared in the sequence yet. SameDirectionGrader will give high grades if the entirety of the notes in the sequence is going up or down. InverseGrader inverts the grade depending on whichever grader is passed into it.

“For instance, if you’re looking for a repetitive electro bassline, you might choose InverseGrader(UniquenessGrader), leading to a high likelihood of choosing the same note,” explains the artist. “Similarly, if you’d like a Dopplereffekt like arp over top, you’d also have another track with SameDirectionGrader. On the other hand, if you’re looking for something more like an Analord funk bassline, you’d go with just UniquenessGrader.”

Here’s an example set of graders that will create acid basslines.

As soon as a note sequenced is chosen, multiple optional mutators conjoined within a set will be applied in order to observe the finished note sequence and will make changes if needed. Some of these alterations might include adding velocity accents or boosting a note up an octave.

A note sequence is spawned for each track on multiple occasions, with one per section. In a typical pop song, it may contain 3 sections of A, B, C arranged as ABABCB. However, in Face Culler’s Procedural Braindance, the number and the order of the note sequences can be hardcoded, but Face Culler revealed to us how exactly he tests around with it.

“More often I leave the number and arrangement of sections to chance.”

The sections employed within the note sequences also define the key or keys for the note sequence generator. On some tracks in Procedural Braindance, the key changes with each bar, and with others each section. “Now we have several sections of music generated. If we were to play the song now, it would sound quite repetitive and also have no overarching dynamic changes, it would sound like section A repeated X times, section B repeated Y times, etc,” revealed Face Culler.

In this part, this is where complexity targets are used. Each note sequence is given a complexity based on how dense it is. With sparse pad sequences, these will have lower complexity, whereas tighter melodies have higher complexity. These complexity values can also be overridden or directly assigned. The starting and ending complexity target is chosen for each section, thus gradually arranging a smooth interpolation of complexity. For each bar, tracks will be randomly added or removed in order to attain the intended complexity value.

“This creates the effect of the track starting with just a few instruments, with more joining in, reaching a crescendo, and then dying off before either picking up again or the song eventually ending,” said Face Culler. The dynamic effect within the tracks becomes infused by running mutators on note sequences right before the tracks drop out, join in, or when the section shifts. For example, for drum tracks, a fill mutator provides a minor alteration to the end of the bar merely before the additional instruments jump in.

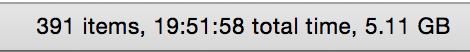

“Finally, once all layers have run, we have a complete song and can begin playing back the midi data. I generally have this hooked up to a bunch of synths (Roland MKS7, Mopho, OB6, Future Retro Revolution, etc) and record them through my trusty Mackie CR1604,” the producer pointed out. Face Culler records 10-20 variations of each set-up, admitting that most of them are just ‘OK’ and within every 5 songs or so, it will really begin to impress. The artist names the tracks based on the arrangements, such as ‘Raven 1’ through ‘Raven 13,’ which are the names you can identify on any Procedural Braindance release.

As you can see, there are quite a few recorded tracks already.

“So far, there has been one free EP on Bandcamp and a CD on Recycled Plastics. I have two more releases, one a bit Tuss like, and one that is more 1970’s library music influenced, that are pending release. Beyond that, there are loads of tunes yet to be generated. I also plan to rewrite Procedural Braindance in C++, or maybe just get it up and running in JRuby, to speed up the generation time (currently 3-5 seconds per song) so it can be used in a live setting more easily,” said Face Culler.

He also expressed his interest in releasing his project as an app as well, by revealing that he made a simplified GUI version, providing his synths at local meetups and acknowledged that it had gone well.